Ancient Echoes: Traces of Queerness in Early Civilizations

ARTICLES | May 28, 2025

PROLOGUE

Ancient Echoes: Traces of Queerness in Early Civilizations

As we celebrate Pride Month and envision more inclusive futures, it is essential to remember that queerness is not new – regardless of what many would like to believe. Far from being a “modern invention”, diverse expressions of gender and sexuality have existed for millennia – coloring the intricate histories of ancient societies across the world. By looking back, we challenge the myth that LGBTQ+ identities are a recent “trend” and instead uncover a rich history of diversity, rituals, love, and complexity.

The Fluid Gods and Lovers of Antiquity

In ancient Mesopotamia, the Sumerian goddess Inanna (later known as Ishtar) was associated with transformation, sexuality, and power. The galla priests who served her were male but performed lamentations in the feminine form and often adopted female names and dress.(1) As activist and scholar Will Roscoe notes, “the worship of Inanna involved crossdressing, gender ambiguity, and ritual lamentation – suggesting a sacred space for gender variance.”(2)

One Sumerian hymn goes,

“To turn a man into a woman and a woman into a man are yours, Inanna.”

– Hymn to Inanna, c. 1900 BCE(3)

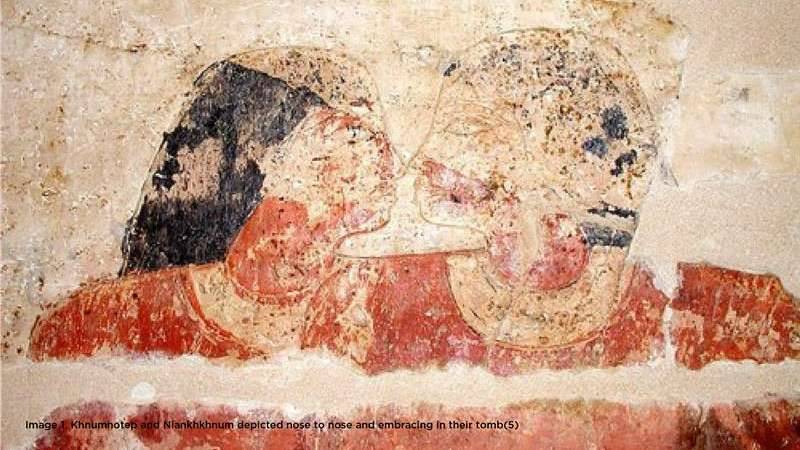

Ancient Egypt offers one of the oldest known depictions of a same-sex couple: Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum, royal manicurists entombed together around 2400 BCE. Their tomb depicts the men in intimate poses typically reserved for married heterosexual couples. Egyptologist Greg Reeder argues that their representation “exceeds standard depictions of close friendship and likely paints a romantic relationship.”(4)

In classical Greece and Rome, same-sex relationships were visible and, in many cases, valorised – particularly amongst men of status. Plato’s Symposium presents male-male love as a pathway to philosophical enlightenment.(6) The Roman emperor Hadrian’s love for Antinous was so intense that after Antinous’s death, Hadrian deified him, establishing cities and temples in his name. “The love of Hadrian for Antinous is one of the most remarkable stories of antiquity,” wrote Margeurite Yourcenar, “precisely because it was public, powerful, and tragic.”(7)

Beyond the West: Global Histories of Gender and Sexual Diversity

While the West often frames queerness as a modern idea, many non-Western cultures have long histories of gender and sexual diversity.

In ancient India, texts such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata reference same-sex love and gender transformation; the deity Ardhanarishvara, half-male and half-female, symbolizes gender unity. “Ardhanarishvara shows that the divine transcends binary gender – an ancient Hindu vision of wholeness.”(8) In modern day India, the Hijra – a recognized third gender community (dating back thousands of years) has held ceremonial roles in weddings and childbirth. Scholar Ruth Vanita notes, “Pre-modern India had a complex and tolerant vies of same-sex love, woven into mythology, religion, and literature.”(9)

In Southeast Asia, Thailand offers its own deep-rooted history of gender fluidity and queer expression. Historical records from the Ayutthaya period (14th–18th centuries) mention court entertainers and performers who dressed in clothing associated with the opposite gender. Some royal chronicles and temple murals depict male couples and kathoey (a Thai term often translated as “ladyboy,” though its cultural meaning is more nuanced) figures in stylized roles. As historian Peter A. Jackson writes, “Thailand has long had indigenous cultural spaces for gender and sexual diversity, though they have been reshaped by Western influence and modern nationalism.”(10) More importantly, the modern visibility of the broader LGBTQ+ communities in Thailand is not a novelty. It draws from a layered cultural past where identities beyond the binary were known and, in some contexts, accepted.

In many indigenous cultures, gender and sexuality were also not binary. Among numerous Native American tribes, Two-spirit individuals – people embodying both feminine and masculine spirits held important spiritual and social positions. Historian Sabine Lang writes, “Two-spirit roles were integral to tribal life before colonization, not marginal.”(11)

Polynesian culture similarly reflects longstanding acceptance of gender diversity. The fa'afafine of Samoa and māhū of Hawaii’ were often embraced as caretakers, educators, and artists. According to cultural historian Niko Besnier, “Gender variance in the Pacific was traditionally normalized – not stigmatized – until colonial and missionary influence.”(12)

Why This History Matters for Our Futures

Queerness is not a recent phenomenon – it is deeply human and deeply historical. The attempt to erase these histories was often intentional, part of larger colonial and religious projects that sought to standardise identity, morality, and power; but these histories are being recovered and celebrated.

When we reclaim these histories, we don’t just honour those who came before – we widen the horizon for what is possible. Queerness has always existed; it will always exist. The question is, how will we build futures that embrace that truth?

As scholar José Esteban Muñoz wrote (paraphrased) in his work on queer futurity,(13)

“The future belongs to those who can imagine it. And queerness has always imagined beyond the boundaries of what is expected.”

Source:

1 Asher-Greve, J. M., & Westenholz, J. G. (2013). Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources. Zurich Open Repository and Archive. www.zora.uzh.ch. https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-135436

2 Roscoe, W. (2000). Changing ones: Third and Fourth Genders in Native North America. In Internet Archive. New York, N.Y.: St. Martin’s Griffin. https://archive.org/details/changingonesthir0000rosc

3 du Toit, H. (Ed.). (2009). Pageants and Processions: Images and Idiom as Spectacle. In www.cambridgescholars.com. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. https://www.cambridgescholars.com/resources/pdfs/978-1-4438-1249-8-sample.pdf

4 Reeder, G. (2000). Same-sex desire, conjugal constructs, and the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep. World Archaeology, 32(2), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438240050131180

5 By Jon Bodsworth - http://www.egyptarchive.co.uk/html/saqqara_tombs/saqqara_tombs_39.html, Copyrighted free use, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4977603

6 Zhao, M. (2024). The Evolution of Love: The Concept of True Beauty in Plato’s Symposium and Phaedrus. In www.claremont.edu. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4815&context=cmc_theses

7 Yourcenar, M. (2015). Memoirs Of Hadrian. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.125737

8 Koolwal, A. (2019). Devdutt Pattanaik, Shikhandi and Other Queer Tales They Don’t Tell You. Journal of Psychosexual Health, 1(1), 90–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/2631831818824457

9 Vanita, R. (2000). Same Sex Love in India: Readings from Literature and History (S. Kidwai, Ed.). Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/ruth-vanita-saleem-kidwai-eds.-same-sex-love-in-india-readings-from-literature-a

10 Jackson, P. A. (2011). Queer Bangkok: 21st Century Markets, Media, and Rights. Hong Kong University Press; JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1xwdfx

11 Lang, S. (1998). Men as women, women as men: Changing Gender in Native American Cultures. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/menaswomenwomena0000lang

12 Besnier, N., & Alexeyeff, K. (Eds.). (2014). Gender on the Edge: Transgender, Gay, and Other Pacific Islanders. University of Hawai’i Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqhsc

13 Muñoz, J. E. (2009). Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. NYU Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg4nr

ACT 1

Erased and Resilient: Suppression and Survival Through the Ages

Queer histories are as old as civilization, but they have not always been told. If queerness has always existed, why has so much of it been erased? To look forward with clarity and context, we must understand how systems of power sought to suppress gender and sexual diversity, and how LGBTQ+ communities respond(ed) with resilience, dignity, and empathy.

This is a story not of silence, but of survival.

Colonization: The Global Machinery of Erasure

Across much of the world, colonial empires did more than just claim land, they imposed new moral codes and legal systems that criminalized what they did not understand (not that they attempted to) – such as gender variance. British colonial rule, for instance, exported discriminatory laws to over 40 countries, many of which still enforce these laws to this day.(1)

“Homophobia was not indigenous to many societies – it was imported.”

----- Dr Sylvia Tamale, Ugandan feminist and legal scholar(2)

In Thailand and much of Southeast Asia, pre-colonial fluidity in gender roles and sexual expression was gradually reshaped by the influence of Victorian-era Western norms, often internalized by the elites.(3) Even in nations never formally colonized, like Thailand, coloniality still operated through education, religion, and international diplomacy.(4)

Religious Doctrines and the Policing of Bodies

Organized religion played a major role in narrowing expressions of love and identity. As Christianity spread through Europe and beyond, earlier cultural permissiveness gave way to doctrinal restrictions.(5) In medieval Europe, same-sex intimacy was condemned and harshly punished.(6) Islamic jurisprudence, though diverse in its interpretations also contributed to the silencing of queer existence in many Muslim-majority societies.(7)

Buddhism, while less prescriptive on sexuality, was often co-opted with moralizing frameworks in Asia.(8) Many institutions absorbed heteronormative ideals over time, even as folk beliefs and popular media continued to reflect gender diversity.(9)

Medicine and the Making of Deviance

The 19th and 20th centuries marked a shift from sin to sickness. LGBTQ+ identities were pathologized by Western science, labelled as disorders to be treated or cured. From electroshock therapies to lobotomies, the “scientific” response to queerness became a new form of control. Even well into the 1970’s, homosexuality remained classified as a mental illness by the American Psychiatric Association.(10)

As historian Susan Stryker says,

“The idea that queerness was something to diagnose gave legitimacy to discrimination – and built institutions around it.”(11) (paraphrased)

Codes, Subcultures, and Survival Strategies

Despite this suppression, LGBTQ+ communities never disappeared. They adapted, creating coded languages (Polari in the UK,(12) Swardspeak in the Philippines(13), underground spaces, and cultural symbols to survive and connect.(14) In Thailand, the visibility of kathoey in entertainment and temple art quietly preserved gender variance even when public discourse could be hostile.(15)

The ballroom scene in 20th century Harlem,(16) the emergence of drag as political art,(17) and queer zines of the 1980’s(18) all reflect a profound truth: when the world silences you, you find new ways to speak.

Resilience as a Foresight Strategy

Today, the study and practice of Foresight is not just about signals, trends, and technological innovations – it is about societal and cultural nuances. LGBTQ+ communities offer some of the world’s most compelling examples of resilience – not just bouncing back, but reimagining systems, challenging norms, and building alternative futures.

By recognizing these historical patterns or suppression and resistance, we better equip ourselves to anticipate future challenges – whether it is digital erasure, algorithmic bias, or the resurgence of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation. Resilience is not just a theme of the past – it is a foundation of what comes next.

Looking Ahead

As we move into the 3rd part of this series, we will explore how queer visibility emerged in the modern world and how movements for justice have reshaped not only laws, but the language of identity and belonging. From Stonewall(19) to social media, visibility has been both a battleground and a beacon.

Sources:

1 Wong, T. (2021, June 28). 377: The British colonial law that left an anti-LGBTQ legacy in Asia. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-57606847

2 Tamale, S. (2013). Confronting the Politics of Nonconforming Sexualities in Africa. African Studies Review, 56(2), 31–45. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43904926

3 Ojanen, T., & Boonmongkon, P. (2014). Mobile Sexualities: Transformations of Gender and Sexuality in Southeast Asia. Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/11497712/Mobile_Sexualities_Transformations_of_Gender_and_Sexuality_in_Southeast_Asia

4 Jackson, P. A. (2010). The Ambiguities of Semicolonial Power in Thailand. The Ambiguous Allure of the West, 37–56. https://doi.org/10.5790/hongkong/9789622091214.003.0002

5 Human Dignity Trust. (2025, February 11). A history of LGBT criminalisation. https://www.humandignitytrust.org/lgbt-the-law/a-history-of-criminalisation/

6 Halsall, P. (1996, January 26). The Experience of Homosexuality in the Middle Ages. Fordham.edu. https://origin.web.fordham.edu/halsall/pwh/gaymidages.asp

7 Zaharin, A. A. M. (2022). Reconsidering Homosexual Unification in Islam: A Revisionist Analysis of Post-Colonialism, Constructivism and Essentialism. Religions, 13(8), 702. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080702

8 Jackson, P. A. (1995). Thai Buddhist Accounts of Male Homosexuality and AIDS in the 1980s. The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 6(1-2), 140–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1835-9310.1995.tb00133.x

9 Jackson, P. A. (2011). 21st Century Markets, Media, and Rights. Hong Kong University Press; JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1xwdfx

10 Drescher, J. (2015). Out of DSM: Depathologizing Homosexuality. Behavioral Sciences, 5(4), 565–575. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs5040565

11 Stryker, S. (2017). Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution (2nd Edition). Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/transgender-history-the-roots-of-todays-revolution-2nd-edition-by-susan-stryker-2017-z-lib.org

12 BBC. (2018, February 13). Polari: The code language gay men used to survive. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180212-polari-the-code-language-gay-men-used-to-survive

13 Catacutan, S. (2013). Swardspeak: A Queer Perspective. ResearchGate; University of the Philippines Open University. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338677861_Swardspeak_A_Queer_Perspective

14 Boellstorff, T. (2007). A Coincidence of Desires: Anthropology, Queer Studies, Indonesia. Duke University Press; JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv125jthx

15 Sinnott, M. J. (2004). Transgender Identity and Female Same-Sex Relationships in Thailand. University of Hawai’i Press; JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt6wqw5m

16 Morgan, T. (2021, June 28). How 19th-Century Drag Balls Evolved into House Balls, Birthplace of Voguing. History.com. https://www.history.com/articles/drag-balls-house-ballroom-voguing

17 CBS News. (2022, October 29). The history of drag, and how drag queens got pulled into politics. https://www.cbsnews.com/minnesota/news/the-history-of-drag-and-how-drag-queens-got-pulled-into-politics/

18 Andersonian Library. (2025, February 20). The Queer History of Zines. https://guides.lib.strath.ac.uk/blogs/library-blog/the-queer-history-of-zines

19 Library of Congress. (2019). 1969: The Stonewall Uprising. Library of Congress. https://guides.loc.gov/lgbtq-studies/stonewall-era

Act 2

Reclaiming the Narrative: Visibility in the Modern World

If erasure was the tool of the past, then visibility is the battleground of the present. The LGBTQ+ rights movements of the modern era have been at their core – a struggle to be seen. Not just as individuals, but as communities with rights, histories, and futures.

In this third installment of our Foresight series, we look at how queer visibility has transformed over time – from riots and resistance to recognition and rights. However, visibility is not the end goal, it is a tool in the long journey toward true inclusion and equity.

From Resistance to Recognition: Pivotal Moments in the Movement

The Stonewall Uprising of 1969 is widely recognised as a turning point in the LGBTQ+ struggle for acceptance and freedom. Sparked by a police raid on a gay bar in New York City, it catalysed a wave of LGBTQ+ activism around the world. Figures like Marsha P. Johnson(1) and Sylvia Rivera(2) trans women of colour often overlooked in mainstream accounts – stood at the frontline of a movement that demanded not just tolerance, but liberation.(3)

“You never completely have your rights, one person, until you all have your rights.”

– Marsha P. Johnson(4)

The HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980’s and 1990’s further galvanised activism.(5) As governments hesitated and public stigma surged, LGBTQ+ communities organised their own care systems, advocacy groups, and protest movements.(6) Organisations like ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) used visibility – through bold graphics, civil disobedience, and media disruption as a strategy of survival.(7)

These decades also saw the slow but crucial growth of legal protection:

• The decriminalisation of homosexuality in various countries (e.g., UK in 1967, India in 2018)(8)

• Marriage equality wins (Netherlands in 2001, Thailand in 2025)(9)(10)

• Gender recognition laws and protections for trans individuals in countries like Argentina, Malta, and increasingly across Asia.(11)

Each legal milestone came through public pressure, storytelling, and the courage of those willing to stand visibly in their truth.

Visibility is Political and Not Without Risk

While visibility can be empowering, it also brings exposure to surveillance, backlash and violence. Queer and trans people who are racialised, disabled, financially struggling, or otherwise marginalised often face the highest risks – even within LGBTQ+ spaces.(12)(13)(14)(15)

This is where the evolving discourse around ‘intersectionality’ matters. Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw,(16) American civil rights advocate and a scholar of critical race theory, in 1989; ‘intersectionality’ explores how multiple systems of oppression: racism, sexism, classism, ableism – intersect and compound. It challenges any singular narrative of the LGBTQ+ identity and advocates for inclusion.(17)

In Thailand, for example, trans visibility in media is relatively high, but this does not necessarily translate to strucutural rights or security. Many trans people face employment discrimination, lack legal gender recognition, and are excluded from health care or military exemption without bureaucratic hardships.(18) Visibility alone does not ensure justice – it must be paired with structural change.

Memory as Strategy: The Power of Remembering

Reclaiming queer history is not just a symbolic act, it is strategic. When we are reminded and remember that LGBTQ+ people have always existed, resisted, and contributed to society, we counter the narratives that present queer people as “recent”, “fringe”, or Western constructs. Historical visibility strengthens the case for inclusion by asserting continuity, legitimacy, and resilience.

“It is necessary to share the power of each other’s history as a weapon against all oppression.” (paraphrased)

– Audre Lorde(19)

In Foresight, understanding history helps us see the patterns of marginalization and envision alternative futures. The struggles of the past teach us not just how far we have come, but what can be lost when progress is fragile. Anti-LGBTQ+ laws returning in parts of the world today are a reminder: visibility must be defended, reimagined, and shared across generations.

Toward Future Narratives: Visibility Beyond Repression

What comes after visibility? As queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz put it, we must look toward “queer utopias”(20) – visions of a world where every single member of society is not just seen, but where everyone thrives.

From pride parades to podcasts, reels/shorts to zoom panels, today’s LGBTQ+ youth are not only inheriting narratives, but they are also authoring new ones. This moment calls for storytelling that centres not only trauma and triumph, but also imagination. The futures are not predictions – they are what we create.

Looking Ahead

In the final installment of this series, we will explore the question, “What does a radically inclusive future look like?” And what role can Foresight play in building it? As we look forward, we will explore trends, tensions, and transformations that could help shape the future narratives of LGBTQ+ communities.

We believe that visibility is not the end goal – it is just the beginning.

Sources:

1 Rothberg, E. (2022). Marsha P. Johnson. National Women’s History Museum; National Women’s History Museum. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/marsha-p-johnson

2 Rothberg, E. (2021, March). Sylvia Rivera. National Women’s History Museum. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/sylvia-rivera

3 Library of Congress. (2019). 1969: The Stonewall Uprising. guides.loc.gov; Library of Congress. https://guides.loc.gov/lgbtq-studies/stonewall-era

4 Chang, R. (2022, January 28). 13 Powerful Marsha P. Johnson Quotes. Biography. https://www.biography.com/activists/marsha-p-johnson-quotes

5 Katz, M. H. (2005). The Public Health Response to HIV/AIDS: What Have We Learned? The AIDS Pandemic, 90–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012465271-2/50007-8

6 White, J., Sepúlveda, M.-J., & Patterson, C. J. (2020, October 21). Public Policy and Structural Stigma. National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566075/

7 Burk, T. (2015). Radical Distribution: AIDS Cultural Activism in New York City, 1986-1992. Space and Culture, 18(4), 436–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331215616095

8 Mignot, J.-F. (2022). Decriminalizing Homosexuality: A Global Overview Since the 18th Century. Annales de Démographie Historique, 1. https://hal.science/hal-03778162

9 Pew Research Center. (2024, June 28). Same-Sex Marriage Around the World. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/fact-sheet/gay-marriage-around-the-world/

10 The Government Public Relations Department. (2025, January 14). Thailand’s Marriage Equality Law Takes Effect January 22. prd.go.th. https://thailand.prd.go.th/en/content/category/detail/id/52/iid/355315

11 Kenny, E., & Bloom, E. (2023, April 3). Explainer: The Crucial Fight for Legal Gender Recognition. www.idea.int. https://www.idea.int/blog/explainer-crucial-fight-legal-gender-recognition

12 Kempapidis, T., Heinze, N., Green, A. K., & Gomes, R. S. M. (2024). Queer and Disabled: Exploring the Experiences of People Who Identify as LGBT and Live with Disabilities. Disabilities, 4(1), 41–63. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4010004

13 Veldhuis, C. B. (2022). Doubly Marginalized: Addressing the Minority Stressors Experienced by LGBTQ+ Researchers Who Do LGBTQ+ Research. Health Education & Behavior, 49(6), 109019812211167. https://doi.org/10.1177/10901981221116795

14 Badgett, M. V. L., Waaldijk, K., & Rodgers, Y. van der M. (2019). The relationship between LGBT inclusion and economic development: Macro-level evidence. World Development, 120(120), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.03.011

15 American Medical Association. (2021, June 24). Black & LGBTQ+: At the intersection of race, sexual orientation & identity. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/population-care/black-lgbtq-intersection-race-sexual-orientation-identity

16 Columbia Law School. (2023). Kimberle W. Crenshaw. www.law.columbia.edu. https://www.law.columbia.edu/faculty/kimberle-w-crenshaw

17 Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: a Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf

18 Holmes, J. (2021, December 15). “People Can’t Be Fit into Boxes”: Thailand’s Need for Legal Gender Recognition. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/12/15/people-cant-be-fit-boxes/thailands-need-legal-gender-recognition

19 Lorde, A. (1977). Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Crossing Press | Berkeley. https://sites.evergreen.edu/mediaculture/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2015/03/AudreLordeSisterOutsiderExcerpts.pdf

20 Muñoz, J.E. (2009). Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York University Press. https://www.vfw.or.at/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Munoz_CruisingUtopia_Introch1.pdf

Epilogue

Future Visions: Queerness as a Lens for Foresight

“Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality. Put another way, we are not yet queer.”

– José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia (2009)(1)

The path from erasure to visibility is not linear and it does not end with representation alone. As we arrive at the close of this series, we turn our attention to the future. What could a radically inclusive world look like? And how might queerness not just survive, but help us reimagine systems, societies, and ways of being?

Foresight is the practice of thinking ahead – of making sense of change and complexity to envision and shape better futures.(2) Queerness is a kind of futures thinking, it challenges the norm, disrupts the expected, and makes space for the not-yet-known.(3)

Together they offer a powerful lens for imagining what comes next.

Queerness as a Foresight Tool: Disrupting the “Default Future”

In Foresight, the “projected/default future” is the one most people assume will happen based on present norms, dominant values, and inherited systems.(4) It is linear, often exclusionary, and resistant to disruption. But queerness, as both identity and critique, questions what is considered “normal” or inevitable.(5)

Using queer futures thinking means asking:

• What identities and ways of living are assumed in future visions?

• Who gets to belong in envisioned worlds – and who is left out?

• What could emerge if we centred difference, fluidity, and care in the design of systems?

In many ways, queer people have always been futurists – crafting chose families (Hānai), alternative economies, and communal survival strategies under conditions of marginalisation. These practices are not only personal; they are political and visionary.

Trends Shaping Queer Futures

In this section, we are highlighting 2 trends from our repository(6) that are shaping the future of LGBTQ+ inclusion – not just as a matter of rights, but as a lens for innovation, resilience, and systems change.

1. Fluid Identities: Post-Binary Societies

From growing recognition of nonbinary identities to the rise of gender-neutral language and legal categories,(7) we are seeing a shift away from rigid gender binaries. Some countries now allow for third-gender passports(8) or gender self-identification without medical gatekeeping.(9) In digital spaces, young people are creating cultures where fluidity is normalized rather than policed.(10)

• What if the futures did not just “accommodate” nonbinary people – but was built with them?

2. Inclusive Technologies: Blurred Boundaries between Physical and Virtual Worlds

AI, biotech, and virtual platforms will shape how we express identity, access services, and form relationships. But these tools can either reproduce bias or unlock new forms of empowerment.(11) Queer technologists and designers are already asking:

• How can algorithms reflect a diversity of bodies and experiences?

• What does consent look like in digital intimacy?

• Can data ethics include queer safety and sovereignty?

Future Scenario: Normative Narrative Approach

When we imagine the futures, we often default to predictions – what is likely, what is trending, what is coming next. But in Normative Foresight, we ask a different question:

What kind of future do we want to live in?

Normative Foresight is the practice of envisioning desirable futures – ones grounded in our values, hopes, and principles of justice.(12) Rather than merely extrapolating from the status quo, it invites us to dream bigger, then work backwards to understand how we might get there.(13) It is not fantasy; it is purposeful imagination.

We believe this approach is especially powerful for envisioning alternative futures – particularly for communities who have had to imagine otherwise. In that spirit, we draw inspiration from the rich history queer people who have created alternative systems of care, family, and resilience – not by choice, but out of necessity.

And so, we offer a vivid scenario set in the year 2045, shaped by queer values: kinship, fluidity, equity, and collective care.

This is not a forecast. This is a future worth fighting for.

------------ The City of Many Kin ------------

June 2045 – in the heart of what was once a chaotic, congested capital in Southeast Asia, the air feels lighter.

It is not the after-cool of the monsoon waves.

Something deeper has shifted: the atmosphere of belonging.

Maya (19 | they/them) prepares to attend the annual ‘Kinship Festival’, a tradition started 15 years ago when the city passed its ‘Plural Belonging Act’. The law did not just legalise same-sex unions – it redefined family. ‘Kinship’, as recognised in legal and civic terms now includes chose families, collective households, intergenerational pods, and care networks.

Every year during Pride month, the Kinship Festival showcases not just colourful art and rainbow flags, but also policy exhibitions. People can tour model policies that started locally but are now replicated globally:

1. Gender-free legal documentation

2. Civic planning designed by marginalised youth

3. Inclusive healthcare that reflects queer, disabled, and neurodiverse needs

4. Curricula integrated with Indigenous knowledge, climate resilience, and creative technologies

Maya’s presentation this year is ‘Futures of Fluidity’, a speculative design piece developed at the Foresight School, one of several community-rooted campuses that have replaced traditional knowledge institutions.

This project envisions what might come next in the futures of ‘move’ and ‘work’,

• Mobility pods that adjust to sensory and emotional needs in real time

• Workplaces that use ‘care credits’ to account for emotional labour, community engagement, and collaborative decision-making

Maya’s vision is not science fiction. It is a provocation – a gentle nudge toward futures shaped by empathy – not efficiency.

Outside the presentation hall, the city itself is already changed and continues to change.

People live in modular co-housing clusters, designed for adaptability and care. Rooftop gardens, shared kitchens, and circular waste systems sustain each other through local trust networks.

Learning takes place across generations – in repair cafés, storytelling circles, and forest classrooms.

Work is flexible, meaningful, and co-created – evaluated not just by output, but by social impact.

Play is integrated into urban life: drag shows in night markets, multilingual open-mic nights, playgrounds designed by children and elders together.

Sustainability is not a department – not a buzzword, it is a shared ethic. Every space, every system, every interaction considers care for people and planet.

The world is not perfect. It is not utopia. But it is alive, and it belongs to everyone.

Queerness is everywhere, but not in neon; it is in how people relate, make decisions, rest and build.

How did we get here? Let us look back to look forward.

The Arc from 2025-2045

2025-2030: Backlash and resilience.

Amid global anti-LGBTQ+ legislations, activists redirect strategy toward municipal and local power. Building city charters that prioritise care economies, gender self-determination, and inclusive design.

2030-2035: Public trust shifts.

After the post-pandemic recovery debacle, people lose faith in centralised systems. Cooperative models, many built by queer and differently abled communities prove more resilient. Governments adapt.

2035-2040: Queer Foresight becomes institutional.

Schools, think tanks, and civic planning bodies begin embedding radically inclusive scenario planning. Reparative futures become fundable projects.

2040-2045: Policy catches up with imagination.

Legal, economic, and educational systems are restructured based on care, fluidity, and kinship – led not by the “powerful”, but by those previously marginalised.

Why This Future Matters

This is not fantastical – it is a vision grounded in lived possibilities. Intersectional and marginalised communities have always built new systems under pressure. The difference in 2045? They are no longer living at the margins; they are designing the centre.

Queer Foresight is for everyone. They are not predictions or utopias, they are provocations. They challenge us to reimagine the rules of what is possible, who matters, and how we live together. They remind us that LGBTQ+ inclusion is not a sidebar to development, innovation, or democracy – it is central to their success.

Conclusion: Visibility was Just the Beginning

As we close this 4-part series, we return to our guiding theme: look back to look forward.

From ancient expressions of gender diversity to present-day struggles for recognition, LGBTQ+ communities have always shaped culture, challenged norms, and modeled alternative futures.

But now, the question shifts, “What world are we building and who gets to design it?”

Foresight when practiced with a queer lens ensures that the futures we imagine are not simply inclusive – but transformational. It reminds us that inclusion is not about making space in an existing structure – it is about rethinking the structure entirely.

And in doing so, we not only dream of better futures, but we also begin to build them.

Sources:

1 Muñoz, J.E. (2009). Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York University Press. https://www.vfw.or.at/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Munoz_CruisingUtopia_Introch1.pdf

2 Kuosa, T. (2011). What is Foresight? JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep05909.7

3 Thomas, R., Lucero, L., Owens, A., & Cahill, B. (2022). Hanging Out with Kids Who Accept Them for Who They Are: Using Queer Theory to Understand How Youth Challenge Norms and Explore Identities. Multicultural Education Review, 14(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615x.2022.2040145

4 UN Global Pulse. (2023). Strategic Foresight Glossary. https://foresight.unglobalpulse.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/UGP-GLOSSARY.v04.pdf

5 Thomas, R., Lucero, L., Owens, A., & Cahill, B. (2022). Hanging Out with Kids Who Accept Them for Who They Are: Using Queer Theory to Understand How Youth Challenge Norms and Explore Identities. Multicultural Education Review, 14(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615x.2022.2040145

6 FutureTales LAB Internal Repository

7 Callaham, S. (2019, December 22). Gender Neutrality: Language, Like Culture, Ever Evolving. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/sheilacallaham/2019/12/22/gender-neutrality-language-like-culture-ever-evolving/

8 The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2022, April 11). Which Countries Offer Gender-Neutral Passports? The Economist. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2022/04/11/which-countries-offer-gender-neutral-passports

9 Ashley, F. (2024, July 2). Gender self-determination as a medical right. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.230935

10 Uzelac, A., & Cvjetičanin, B. (Eds.). (2008). Digital Culture: The Changing Dynamics. Culturelink | Institute for International Relations. https://www.culturelink.org/publics/joint/digicult/digital_culture-en.pdf

11 White, S. K. (2025, March 20). QueerTech empowers queer technologists to thrive in tech. CIO. https://www.cio.com/article/3850453/queertech-empowers-queer-technologists-to-thrive-in-tech.html

12 UN Global Pulse. (2023). Strategic Foresight Glossary. https://foresight.unglobalpulse.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/UGP-GLOSSARY.v04.pdf

13 Gaßner, R., & Steinmüller, K. (2018). Scenarios that tell a Story. Normative Narrative Scenarios – An Efficient Tool for Participative Innovation-Oriented Foresight. Envisioning Uncertain Futures, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-25074-4_3